Recently, a group of environmental enthusiasts were invited to join Chris Peter, the Research Coordinator at Great Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve (GBNERR) for a walk in the marsh at the Great Bay Discovery Center. For many of us, this was our first time actually walking through the marsh, and it was a very exciting experience for all participants on a beautiful autumn day.

Outfitted in knee-high mud boots, the group walked along the marsh and mudflat border to minimize the effects on sensitive low marsh plants. We began exploring, looking under rocks and seaweed in the area of the tidal mud flats to find mud crabs, green crabs, mussels, horseshoe crabs, mud snails, barnacles, and common periwinkles. We also found soft shell clams, oysters, and razor clams.

Chris, who was joined by other staff at GBNERR (Kelle Loughlin: Education Coordinator/Director, Beth Heckman: Assistant Education Coordinator, Jay Sullivan: Naturalist), shared his knowledge of the benefits of salt marshes, explaining that marshes are a breeding ground for animals, such as the ones that were found along the tidal mud flats, as well as for a variety of juvenile fish (mummichogs, killifish, sticklebacks). Salt marshes also provide habitat for commercially and recreationally valuable fish, such as striped bass, as well as birds of prey, such as bald eagles, osprey and herons. Additionally, salt marshes help improve water quality by filtering out sediments and excess nutrients from residential fertilizers, waste water, and agricultural lands.

Chris introduced the group to a refractometer, which we all had a chance to use to measure the salinity of both a salt marsh pool and groundwater. As part of Chris’s research, he uses the refractometer for the long-term measurement of salinity, which is important in determining if climate change is affecting the salt marsh. Of particular interest to Chris and GBNERR is the effect climate change has on sea level rise. If the sea level rises, then the salinity of the marsh moves landward, causing trees on the upland edge to die off (see photo below), changing the plant community.

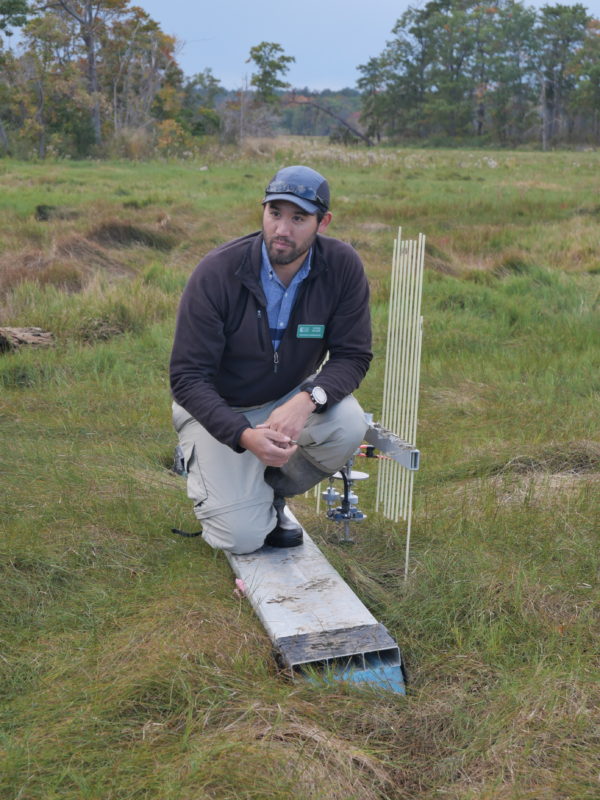

Chris is currently researching how salt marshes in Great Bay, as well as throughout New England, are responding to sea level rise. Chris introduced the group to a surface elevation table (SET), which is able to measure long-term elevation change. Salt marshes build vertically through capturing sediment from runoff and tides as well as plant biomass. SETs inform us if salt marshes are able to keep pace with rapidly rising seas. Chris, along with scientists at UNH, is also researching a unique approach to monitoring fish and crab communities in the bay by collecting their DNA in water samples.

It was clear to all the participants on the marsh walk how lucky we are to live in an area with an estuary in our backyard, and the ability to use these resources year round (kayaking and ice fishing, anyone?).

-By Lauren Saltman, Administrative Coordinator

About Chris Peter

Chris Peter has spent his career researching, protecting and restoring vital aquatic habitats including Great Bay. For the past ten years, he has worked at Jackson Estuarine Laboratory where he conducted research, monitoring, and restoration projects throughout New England. Most recently, Chris was part of a team working on innovative ways to restore salt marshes on Plum Island in Massachusetts and monitoring the resiliency of beaches in New Hampshire and northern Massachusetts. Chris tries to spend all his free time outdoors – hiking, backpacking, running, biking, kayaking, and all activities involving snow.